In the Press

How out-of-work drag performers are lifting fans up through online pandemic shows: ‘A time to be creative

Posed recently on a Facebook community page for the town of Provincetown, Mass. — a seaside getaway known for its mix of beaches and LGBTQ culture — was this refreshingly fun and hopeful question: “Someday in the future, when there is a drag show about COVID-19 …what will be the name of the show?”

Among the 60-plus quick-witted responses: “Queen Corona.” “Mask Hysteria.” “Covidiva.” “Pam Demic.”

Such a show — any live drag show, for that matter — will be a long time coming. But in the meantime, drag performers whose careers have been temporarily sidelined by the coronavirus pandemic have been digging deep for clever ways to support themselves and each other, and to continue to provide a sense of community through the beloved form of entertainment for their ever-growing fanbase.

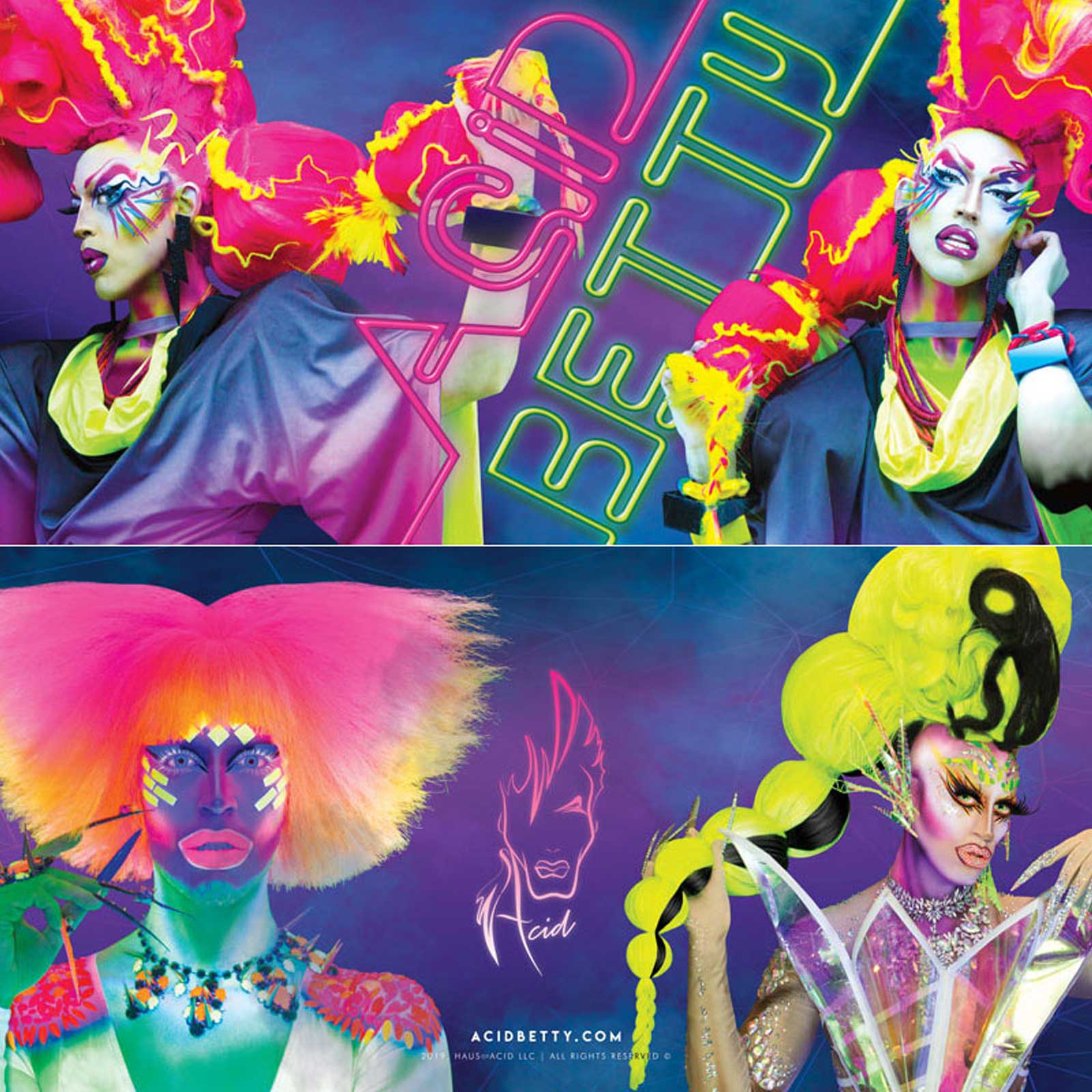

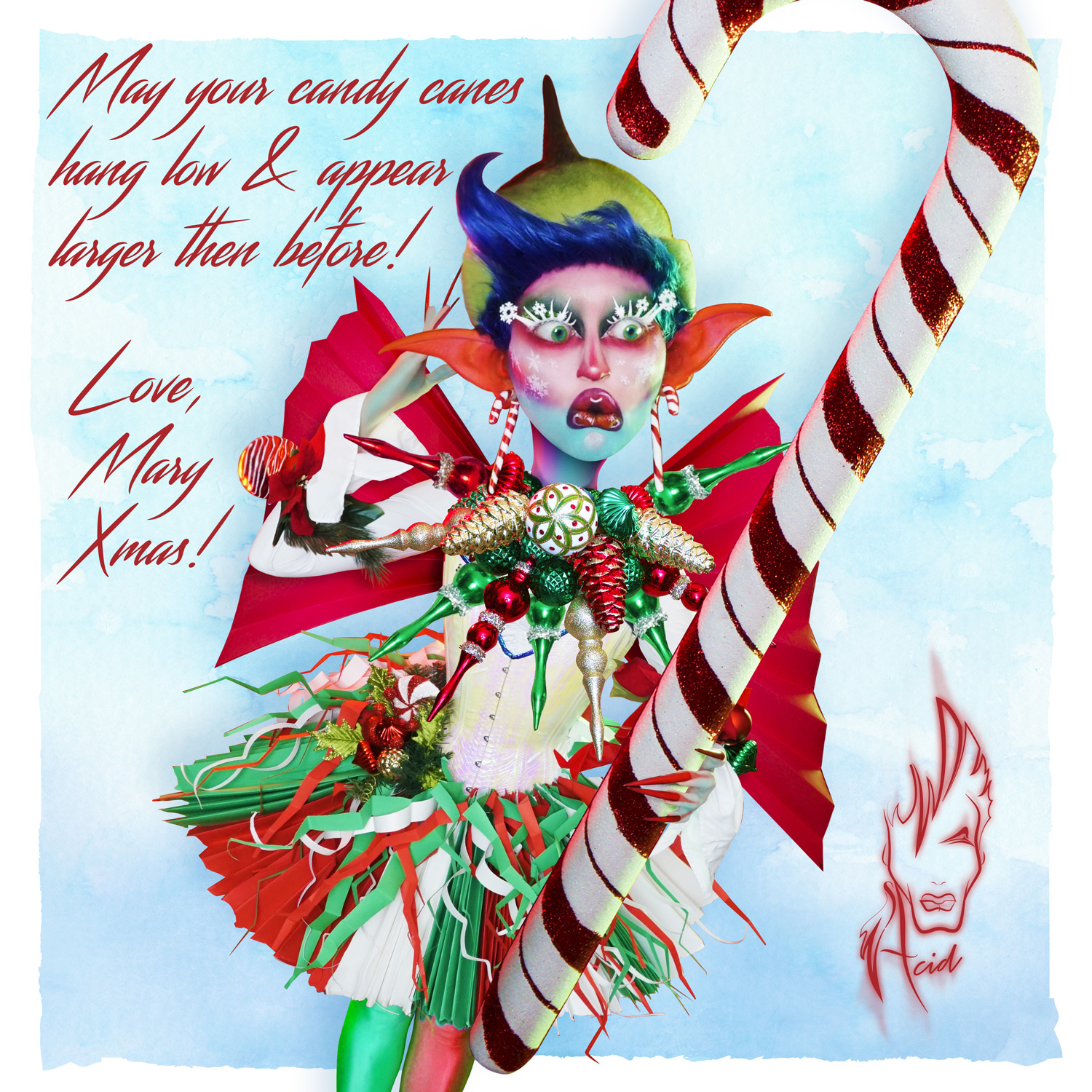

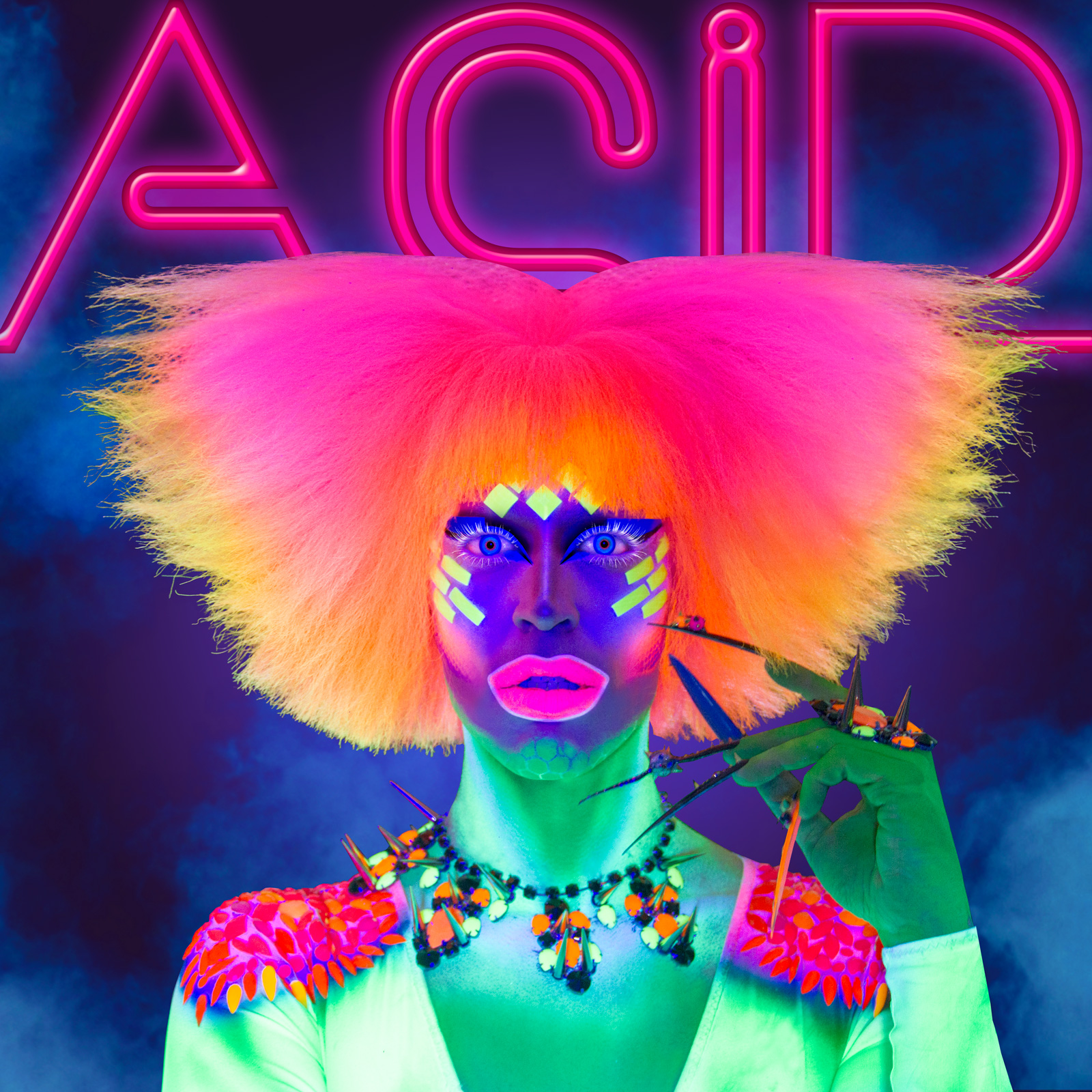

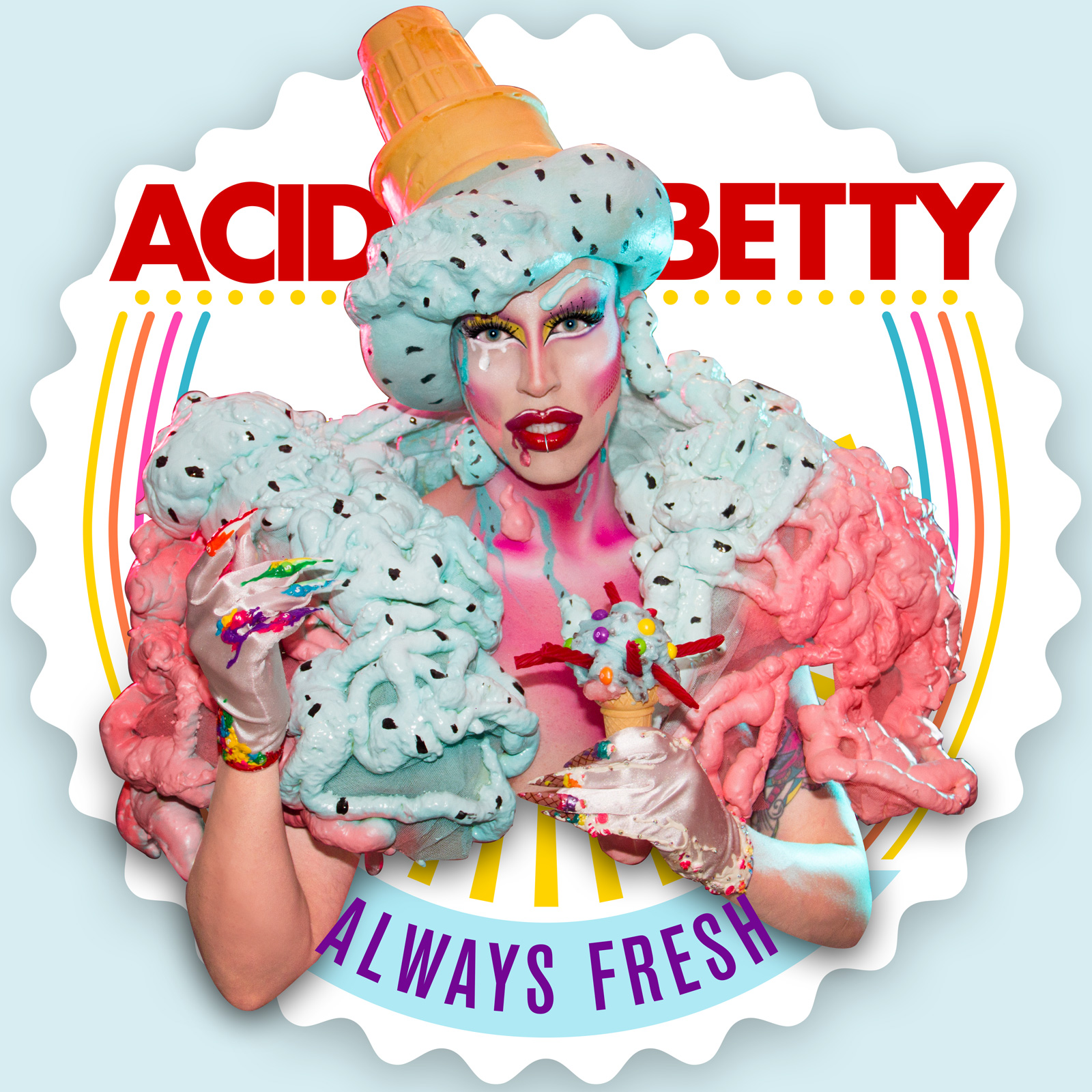

“Drag queens have always been very resourceful,” Acid Betty, the Brooklyn-based provocateur who rose to prominence during her turn on RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 8, tells Yahoo Life. “Some of us already have streams of entertainment online via Instagram, Facebook and YouTube. Once the lockdown began, the surge of online ‘digital’ drag flooded in.”

For Betty, the adjustment has meant pivoting from monthly live performances and producing background visuals for Werq the World: RuPaul’s Drag Race Live to producing visuals for the new Werq the World live streams that benefit out-of-work drag performers — and even creating a line of holographic iridescent hand-sewn face masks that she’s selling online for $20 to $25 a pop.

For other drag artists across the country, it’s meant going from live, paid, hosting and performing gigs to requesting Venmo donations for new online variety shows, bingo nights, drag brunches, story hours, wine tastings or trivia games — on Facebook Live, Instagram Live, YouTube, Zoom or a combination of several. Another platform, Stage It, which is set up to charge nominal viewing fees for performances, has been in the midst of offering a weeks-long Digital Drag Fest, set to conclude on May 17 with Bob the Drag Queen — who has added live virtual shows on both Facebook and YouTube to her busy lineup (not to mention costarring in the new HBO series We’re Here).

Drag performance, which was once upon a time strictly the domain of queer-nightlife goers, has long spread its wings, enveloping much of mainstream America in its span, thanks in no small part to the popularity of RuPaul. It began way back in 1993 with the song “Supermodel” and exploded in more recent years with RuPaul’s mini-empire, including Drag Race (now in its 12th season), Werq the World tours, and the popular conventions DragCon New York and Los Angeles, the latter of which became a two-day digital event earlier this month, with a lineup of more than 70 performers giving their best virtual realness on YouTube to half a million viewers. (It was also just announced that RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 12 finale and reunion specials will air as pre-recorded virtual events, complete with chit chat about life in quarantine.)

“All it took was a global pandemic for me to see DragCon,” one apparently pleased commenter noted.

Since the pandemic took hold in the U.S., the growing offering of online drag events has run the gamut — including homespun living-room sessions, like those from Chevelle Brooks in Houston, Texas and Jewels of Long Beach, Calif.; group lineups hosted by organizations or temporarily-shuttered clubs, such as Quaran Qweens out of Charlotte, N.C., and Local Queen Merch; plus highly produced, interactive events construed as fundraisers for drag performers.

One such notable offering was the recent Virtual Drag Brunchseries (in lieu of the real-life version that had been taking place in NYC), hosted by Drag Race superstars Kim Chi and Naomi Smalls and with shopping-app Klarna donating $1 per attendee, up to $5,000 per brunch, to a drag-entertainer fund. “Klarna actually reached their goal and are donating $15,000 to drag entertainers that are out of work during these trying times,” a publicist for the event tells Yahoo Life. Brunch producer Voss Events is now offering a selection of on-demand digital drag shows as additional fundraisers.

For the many performers involved, the massive shift from live audiences to digital has required a heavy dose of positivity and faith.

“I think there’s going to be a big shake-up in the drag world right now. In order to survive, you’re going to have to be able to provide some kind of cyber fun,” Linda Simpson, a longtime New York City performer who has gone from hosting private parties and popular bingo nights to being “stripped of all my income,” and moving the bingo, plus a growing trickle of other gigs, online. “I realize the health crisis sucks for all performers, but the bright side is that it’s a time to be creative.”

FiFi DuBois, accustomed to performing before large audiences at NYC club, has found the move to online both jarring and heartening. “It’s tough, because drag can be expensive, and with a lot of these shows there is no base pay — it’s all tip-oriented,” she tells Yahoo Life, “so you are literally relying on the kindness of strangers, and most are struggling financially — not just us queens.” But as the bars and clubs she worked with shut down, DuBois started making guest appearances on friends’ shows, eventually parlaying her talent into her own groove; now she does a classic one-woman show on Fridays and a Disney trivia game on Sundays “with real prizes.”

Joe E Jeffreys, drag historian and videographer who teaches courses on queer theater at New York University and the New School, explains that the lasting importance of drag is that it taps into a magnetic power. “Drag performers out on the streets or performing live in bars and clubs…offer a one-on-one, interactive, in-your-face embodiment and challenge to gender systems. They directly confront a ‘one of these things is not like the others’ dynamic that is often startling and always brave.”

That direct “confrontational presence,” he says, is of course watered down during these stay-at-home times. “Drag’s ability to center a local community in gathering places like bars is diminished — while at the same time its potential, via web shows and broadcasts, to attract international audiences in digital spaces is enhanced.”

Performers agree it’s a double-edged sword. “You lose that human interaction and the energy from a live audience,” notes DuBois, with Betty adding, “Live theater is always electric. There is an edge of something can go wrong in addition to being in the room where magic is created just for those who are there to witness it.”

Still, every performer interviewed for this piece said that their audience had grown, in some cases to encompass new fans from around the world.

Says Simpson, “My audiences have tripled in size in comparison what I used to get at my weekly live events.”

Payton St. James, a performer in Provincetown with the long-running drag revue Illusions (the future of which is up in the air for the summer), has found that going online has made it possible to “almost be more creative because you’re not under any time constraint of the show, space on the stage, that kind of thing,” she says. “You always have to try to find the silver lining.”

As far as how the coronavirus pandemic will affect drag’s widespread popularity, Jeffreys says, it’s hard to predict. “Local drag performers’ increasing move to digital shows will hopefully build new audiences eager to see them live when things are safe and people comfortable gathering in bars, clubs and theatres again,” he says.

At the same time, he laments, “during and after the pandemic, drag could become viewed as not relevant to the state of the world — a frivolous and flippant extravagance worthy of ridicule and derision. Let us hope this does not happen. I believe drag’s subversive gender critiques and community building abilities are qualities that will always see it, its practitioners and audiences rise — again and again.”

Or, as Betty puts it: “For those who laugh and say drag is unnecessary? You did just laugh. And that is always necessary.”